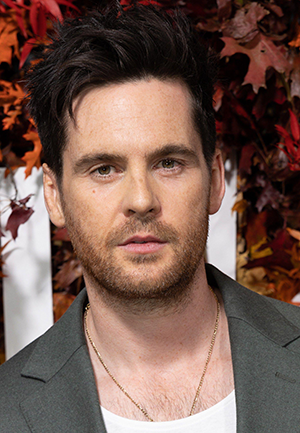

The Genesis Foundation website published an account, written by Tom, of his second year experiences at LAMDA.

Saturday, 11 March 2006

At the end of my second year at LAMDA, when my class was told that for the 'Long Project' (only one important module of our three year training, the one in which the year - in collaboration with a playwright and director - devises and performs a new piece of writing) we would be working with Mark Ravenhill, there was a slight unease.

Mark is a controversial playwright of huge renown. Very much in the tradition of what the theatrical journalist Aleks Sierz - coining a new phrase -“ characterized in the mid-nineties as the 'In-Yer-Face' writers, Mark Ravenhill's plays all had caused tremendous shock waves.

Therefore, at the same time that we felt hugely privileged and excited, there was a bubbling undercurrent of fear about which one of us would inevitably have to strip naked and perform the kind of acts onstage that would make our mothers ring the school and withdraw us immediately from a shameless den of filth. As it turned out, 14 weeks later, the finished piece would barely include a single swear word and would be a giant departure from Mark's previous work stylistically if not thematically. On top of that, it would turn out to be not only an amazing and thrilling learning experience for us all, but also to be an excellent play that we could all be incredibly proud of.

Mark began the rehearsal process with a few basic improvisational games and exercises. He had a few ideas about the direction in which he wished the play to head, but no concrete ideas as yet -just a deadline and 26 expectant actors every day, for eight hours a day. He confessed to being fascinated by capitalism and by big business and the way it shapes our world. We dabbled with celebrity and the cult of showbiz magazines. He suggested we interview each other as various real-life characters. We attempted to plough through books on international economic politics.

A few weeks in, although we had come up with a lot of useful and through-provoking stuff - both entertaining and insightful - it was clear that we still had no solid foundation upon which to base a two hour piece of theatre. Although nobody wanted to admit it, the excitement that had so characterised the early stages of rehearsal was beginning to ebb away and be replaced with the fear that we might never come up with anything.

The following morning, Mark brought in a script he had written previously, inspired by the story of the building of the Millennium Dome. It was an abstract piece between two people that Mark had a feeling could be the springboard into something else. He informed us that we would all be heading to Greenwich to have a look at the Dome and to interview anybody we came across for their opinions on the ill-fated project.

That Friday, we sceptically headed over to South East London to research something that didn't really interest any of us, and we weren't even sure it interested our playwright that much. As far as we were concerned the Dome was a defunct issue, a subject relevant four years ago, but in no way interesting to an audience today. There was a niggling feeling that Mark had packed us off on a day trip to distract from the fact that we had all hit a creative brick wall.

However, the day of interviews was far more enjoyable than we had anticipated, and we all came back re-energised, with a collection of fantastic characters and stories - pulled from the local pubs, shops, schools and youth centres - if not yet with a central theme.

As the weeks drove on, we all began to pull together more and more towards a common goal. This was the topic that had been decided on, and there was no time to start again.

However, the more we discovered, the more interesting the subject became, and the more relevant both to today and to the original themes we had worked on at the beginning of the process, it all seemed to be. We interviewed the great and the good - from politicians to PR guys, policemen to architects, from the chief executive to the man who ran the ice cream stall outside. Everybody had an opinion, and everybody had a revealing story that perhaps had never been spoken about before. Indeed, when I was interviewed by the daily newspaper, The Independent, about the piece some months later, the journalist I spoke to admitted that some of the stories the interviewees had happily surrendered to a collective of wide-eyed actors were the sort of exclusives the papers would have killed for half a decade previously.

As the transcripts flowed in, and the cast improvised with the characters and the situations that had been related to us. Mark began to collate the interviews together into a story - the arc of which would be the ten years from the Dome's conception, through to its disastrous opening night and up to the present day.

It was decided that the acrobats who had been trained specifically for the central show would provide the emotional core for the story, whilst the relationships of those who endured the project from start to finish would be examined throughout the play. On the outskirts various bit-players would fill in the story, progress the plot and provide differing opinions, shedding light both on the Dome itself, and on the state of the country that produced it.

All the while, every single word spoken was real. We had really listened to damning reports on the executive board from the creative director, we had really heard how the Dome affected the Muslim community in Greenwich, and we had really suffered a shower of racist opinions in a local pub. The more pages of the script that Mark delivered to the cast and to Peter James - Principal of LAMDA and the director of the piece - the more we came to realise that, despite appearances, the play wasn't really about the Dome at all. Instead it had become a study of,

- on an emotional level: human nature and relationships

- on a political level: Great Britain and its government - questioning the very functionality of a country that could indulge in such a poorly managed project, whilst simultaneously commenting on the money-hungry American company that takes it over, and

- on a social level: the very structure of British society itself is examined - from the fat cats at the top of the ladder to the lowest labourer, from Islam to Christianity, and from millionaires to those in the dole queue.

In other words, a play that we felt would be about a best-forgotten tent in (as one character so eloquently puts it) "the arsehole of nowhere", had instead turned out to be a hugely relevant piece of political theatre, a metaphor for New Labour and an extremely funny piece of entertainment, wrapped up in a typically dark Mark Ravenhill exterior. And all the while, not a single word was fiction.

We went on stage at the end of the eight weeks confident that we would be performing something amusing, if nothing else. The last few pages had arrived a few days previously and we had been desperately staging them in an attempt not to look as haphazard as the audience were expecting. They knew it would be a workshop production and expectations were set at a certain level accordingly. Neither they nor we could have imagined the reaction. The response was overwhelmingly positive, and all 26 of us were overjoyed that all the hard work had paid off - indeed, the news that North Greenwich would be one of our first public shows in our final year was no longer viewed with trepidation, but with nervous anticipation. I for one had loved the process, and was hoping upon hope that I would be cast in it come September.

The hoping paid off. Mark rewrote the play over the summer break, and brought it in to Peter on the first day of our third year. A play for well over 20 people had been reshaped into a play for eight. Four men and four women would play all 80 parts - a fantastic challenge and an incredible opportunity. The play was tighter, better structured, and if possible, even more in touch with its rousing political and social themes as a result of its streamlining. It was to have a basic, minimalist set, eight chairs facing the audience and all black costumes. The huge number of roles would have to be inhabited without the aid of make-up or costume. In fact, the only indulgence in the play was a large black and white print of the Dome that would be revealed halfway through the first act to the sound of fanfares and a display of lights. It was an incredible gift of a showcase for the eight of us, and one that we all remain hugely grateful for.

The rehearsal process was smooth and enjoyable, the characters that we had played previously familiar enough to allow us to experiment with the new ones that had been played by our friends a few months previously. In fact, it was more of a challenge to erase the memories of some of the excellent performances others had put into the character you were now playing than it was to come up with a new one!

The first night was terrifying, not least of all because the nature of the play meant that it was written as a direct address to the audience. Mark had brought various friends of his from the industry, so to step out in front of our first public audience in three years and come face to face with the Artistic Directors of the National Theatre and the Royal Court was enough to make eight pairs of legs very wobbly indeed.

After our three show run at LAMDA's MacOwan Theatre we went on tour with the play, as part of an initiative whereby we learn to perform in front of a new audience in different spaces. Due to the fact that this idea is in its infancy, it was only for one performance in Bowness, up in the Lake District, which was probably best, as unlike the other two shows that were being performed in rep with ours, we had quiet a bit of trouble getting anybody in to see our new piece of writing. For some reason, a new play by an infamously controversial playwright wasn't that appealing to a little village in the North of England.

It was a very odd experience indeed, as after the massive success and sell-out audiences we'd enjoyed in London, the theatre having to give away a free ticket to our show to anybody who had purchased one for the other two was a little disheartening.

When people did turn up, however, they seemed to be pleasantly surprised - as were we. Early reactions in Bowness had convinced us that Greenwich's main failing was that it was inescapably a politically London-centric piece. However - when we did finally get an audience in they absolutely loved it - laughed harder than any of the London audiences and were thoroughly appreciative after the show. It seemed that no matter where you come from in the United Kingdom, little appeals more than being able to laugh at a Great British cock-up...

We came back from the Lake District extremely sad to have to say goodbye to the play. We had lived with it for six months and, at the risk of sounding overly-melodramatic, it will stay with us a lot longer.

It was, and remains, one of the achievements I am most proud of in my life, both inside LAMDA and out, and I will always feel extremely lucky to have not only worked with Mark Ravenhill on a new play, but to have actually been part of the team that conceived, researched and performed it.

As chief executive of the Dome, Jenny Page, states upon her resignation from the Millennium project: "There's a sort of sense that after the Dome you can't settle down to an ordinary job again. The world is a slightly different place..."